Can Writing Be Taught?

It is not uncommon to read a book on writing that will preface itself with the idea that writing — and more specifically great writing — cannot be taught. It’s an attitude that I think stems from the misplaced idea that writing is a mysterious gift, one that bubbles up from some unknown place within the writer, which cannot be replicated or taught. You simply have that gift or you don’t. But it’s a strange attitude. Why is writing unlike any other skill, so mysterious up on its pedestal? The fact is, it’s not.

As much as writing is my first and only love, what I pray to daily, alone in my room, with the regularity of a fanatic, there is nothing inherently special about it. That pains me to say, but I know it to be true.

It is a skill you work at, which over time, given the work, you will get better at. Around every writing corner, there are secrets and there are many opportunities where learning can (and must) be done. There are skills and lessons to improve on and progress to be made. And if all of these exists, that also means there are those that have already uncovered them, gone through the process, and can teach them to you (or you to yourself).

The article could end here, but I’d like to dive deeper into what others think on this subject, both for and against the motion, what I think personally, and if writing can taught, where should one start?

Those that think writing can be taught

Ira Glass has what is possibly my favourite lesson for anyone approaching a new skill, art, or passion.

Instead of butchering it, I’d prefer to just share it in its entirety because it’s just that good.

Ira Glass, award-winning radio host of This American Life, story teller, producer, writer, and all around talent, has a very clear message. When you first start writing, you’re going to suck, but you got into writing because you love reading stories (and if you didn’t, rethink what you’re doing here). He believes that as long as you can survive the artistic “gap,” as he calls it, where what you produce is worse than what your taste tells you is a good work, you can become good.

That’s an important lesson to realize. You will suck—but that doesn’t make you unique or inadequate. We’ve all gone through this process. I’m still going through this process. But what you have to believe is that you can learn how to get better, as long as you stick it out through the so-called “gap” in your talent and taste.

Steven King classified writers (of all stages) as bad, competent, good, or great. He believes you can move from one spot, from bad to competent or competent to good, but unless you have an innate greatness in you, you’ll likely never be great.

I’ll say two things here: those that are classified as great are rarely done so in their time.

The second thing is: who cares. The greats include such venerable writers like Shakespeare, Melville, Tolstoy, Dickens, Dostoevsky, and so on. I doubt even King puts himself in the great.

The goal, or the question, isn’t “can everyone be great?”

Of course they cannot. Not everyone can be Lebron James or Michael Jackson or John Lennon or James Joyce and you shouldn’t set out striving to be these people, because I doubt that’s where they started. You simply start out wanting to do, then along the way someone, be it a mentor or a teacher or yourself, realizes you have the capacity to be great.

Then you become great by focusing on yourself and what you can accomplish.

And as a side note, all stages of writers get published and struggle to get published. Bad ones get published AND read — there’s the Twilights and 50 Shades Of Greys of the world. Books by competent writers get published. And good and great writers struggle to get published.

The first print of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick ran 500 copies, but only sold 300 and he died thinking himself a literary failure. The Great Gatsby was the same, with Fitzgerald dying thinking he and his work had forgotten. Then the book was distributed to the army during World War 2, and became part of the US high school curriculum. Kafka was never successful during his lifetime, and despite telling his friend and publisher Max Brod to burn his books because he believed them to be trash, he has posthumously become a literary giant.

Writers Rivka Galchen and Zoe Heller tackle the question in the NY Times Bookends series.

Rivka Galchen makes an interesting comparison to other school subjects, like sports or the sciences. In these, we do not think our goal is to create masters, but to teach the basic rules, and to convey the creative process, of writing.

Zoe Heller put it well, when she said that, “No one seriously disputes that good writing has certain demonstrable rules, principles and techniques.” In so far as that is true, then absolutely writing can, and should, be taught.

Writers and writing teachers often mistake the goal of the creative writing class. It is not to create masters. It is simply to teach the basic rules of craft and guide a writer in their own pursuits.

So the question isn’t just “can writing be taught?” but “can the writer learn to write better?” And both seem to be true, regardless of the possible objection “how much better?”

Those that think writing can’t be taught

“Is it just that it’s somehow flattering to feel one’s endeavor is more gift than labor, and are writers more in need of such flattery than others? Possibly.” — Rivka Galchen

This entire question, the idea of “can writing be taught?” started with an article I saw posted in the Stranger written by Ryan Boudinot. It was called: “Things I Can Say About MFA Writing Programs Now That I No Longer Teach in One.”

I read it when it was originally posted in 2015 and it has always stuck with me, so if nothing else, I’d love to go through each point one by one and see where we agree and disagree—especially now that I’m in an MFA program myself.

His first point is “Writers are born with or without talent.”

This is true of any endeavour ever known to man, and it’s so true as to be irrelevant to bring up or care about. You’re born with the talent you have, so stop fretting about what talent you do or don’t have. Learn to work with what you have and move on. Besides, talent in writing, like in all things, comes in many forms.

To make a very clear analogy, the basketball Muggsy Bogues was middling basketball player with an average career—except for one thing. He was 5 foot 3 playing with giants. He talents did not include the gift of god-given height. But he made up for it in other ways.

The point is, talent comes in many forms. The sooner you get over what you’re lacking and discover where you are talented, the better you’ll be.

Are your prose lacking? Fit a character’s voice to dry prose. Is it creativity? Remake a classic story and fit it to your own voice and vision, with your own characters. Do you lack an ability to understand characters? Write science fiction about aliens no one understands. Do you have robotic dialogue? Write about Artificial intelligence.

See where I’m going? We all lack talent. We all have things to work on. Figure out a way around yours.

Second, if you complain about not having time to write, please do us both a favor and drop out. This seems so self-evident, that it’s silly to state or put into a scathing article about how your students are terrible. If you don’t have time to practice any skill, you’re not going to get better. If you don’t have time to study physics, why are you in a masters program for physics? This doesn’t seem like a revelation that it would take teaching an MFA program to come upon.

Third, if you didn't decide to take writing seriously by the time you were a teenager, you're probably not going to make it. This is self-evidently not true. You’ll find many late bloomers to many different professions. I also have a personal stake in this being not true, because I came to writing at twenty seven, and I believe in the time I’ve spent learning the craft, I’ve progressed wonderfully.

Fourth, it’s not important that people think you're smart. I actually really like this piece of advice. Trying too hard in writing is obvious. And if I could give one piece of writing advice to the newer writer it would be this: try to have fun instead of trying to sound smart.

Fifth, it's important to woodshed. That is, writing takes time, it takes practice, and it takes effort, which is why I again think it’s strange for an MFA professor to judge someone’s ability to improve within a 3 month time period of a class. That’s not enough time to notice any real discernible improvement, especially when you’re in the ‘competent - good’ stage and progress comes in inches.

Last, if you don’t have time to read, you don’t have time to write. Agreed. It’s as simple as that.

Concordia University professor Kate Sterns answers simply, “No.” Watch her answer here.

She has a quasi-good answer that I agree with. Writing, in a sense, isn’t taught but guided—though I think that only comes after a certain part. The basis of a lot of writing will be taught. To refer back to King’s ordering, to go from bad to competent can surely be taught, but going from competent to good may be a matter of guidance, not teaching. Those writers need to be steered in the right direction, so that their own talent, their own voice, and their own creativity can flourish.

This does create a somewhat of a tricky situation for writing programs like MFAs, but my experience so far is somewhat in agreement withKate, in that writing isn’t being taught so much as guided. Everyone in these programs are presumably already at an adequate or good level. They merely need the creative time, space, or surroundings to move to the next level.

And I believe she hit the nail on the head here when she says the MFA program “provides the space to flourish.” That’s actually what convinced me to take an MFA program. It was Jane Friedman who made it clear when she said it would be the only time in your life that you get to focus entirely on your craft. And that’s what I want. The room to learn.

Finally, let’s look at one last grumpy old writing professor, Hanif Kureishi, who says “creative writing courses are a waste of time.”

Hanif’s main point is that within creative writing courses, what happens is you learn little, write little, and exchange ideas with other members of a workshop that don’t know how to write either.

I think that’s true to an extent, but that’s also why everyone is there. To learn, to form community, to meet other people who plan to take writing seriously in the future.

He also goes as far to say that “a lot of my students just can’t tell a story” which, to be blunt, is an idiotic statement that misses the point of what taking classes are for.

Students are there because they want to learn how to write a story. And his job is to teach them. If he’s starting from a point that everyone is unteachable, he’s always going to have a hard time teaching them.

Especially because most stories are simple formulas, which have simple rules, and are absolutely teachable.

Do I personally think writing can be taught?

I think it’s already rather apparent that yes, I do believe writing can be taught. Absolutely yes. In fact, having just switched out of digital marketing into full time writing, I’m betting my entire career and livelihood on it.

When I think about what makes us human, I think it’s precisely those things that surround writing: language, expression, story-telling, emotion, creativity. We’re born with these abilities to varying degrees, but we all have them.

And language itself, which is the building block of any writing craft, is intrinsically (and literally) tied to a child’s development. We know where a child is at because of where they are in their language production.

What’s more, our capacity for language is what separates us from animals. It’s our essence and if our essence cannot be taught, cannot be improved upon, cannot be learned, human society wouldn’t have progressed over time.

We’re taught writing from an early age, up until we’re adults and then some. If this wasn’t the case, what a gargantuan waste of time we’ve all undertaken. If writing couldn’t be taught, what are we all doing in English classes all around the world, reading books, attending seminars or workshops, studying grammar, or sitting down to write every day of our lives.

To me, it’s strange that the question is even asked (though I suppose I’m somewhat responsible for asking it).

But why, if it’s so obvious, are we inundated with those who we revere, those who have accomplished something in the field, those who should be there to teach us, telling us that they have knowledge that is on some level unknowable?

I think what it comes down to is not that writing can’t be taught, but that unique thing that you have to say, that original voice, whatever it is that makes your story worth telling, that cannot be taught to you because it is inherent to you.

What can be taught is creating the personal and material conditions to let those internal and intrinsic aspects flourish within you and let that unique voice out.

What people are saying when they say writing can’t be taught is simply mistaking the fact that their own unique creativity, that thing that makes what they do unique, cannot be taught. And that’s okay. Because you don’t want their voice. You don’t want what makes them unique. You want your own voice, which you can development in time.

So then if writing can be taught, where should one start?

I think there are four aspects to a writing practice: the habit of writing, reading books on writing, reading fiction like the kind of books you want to write, and writing itself.

So let’s briefly go through where I think a beginning writer should start with each of these.

The daily habit of writing

It takes work to sit down every day and write, so here are the best ways I’ve found to improve the consistency of that daily habit.

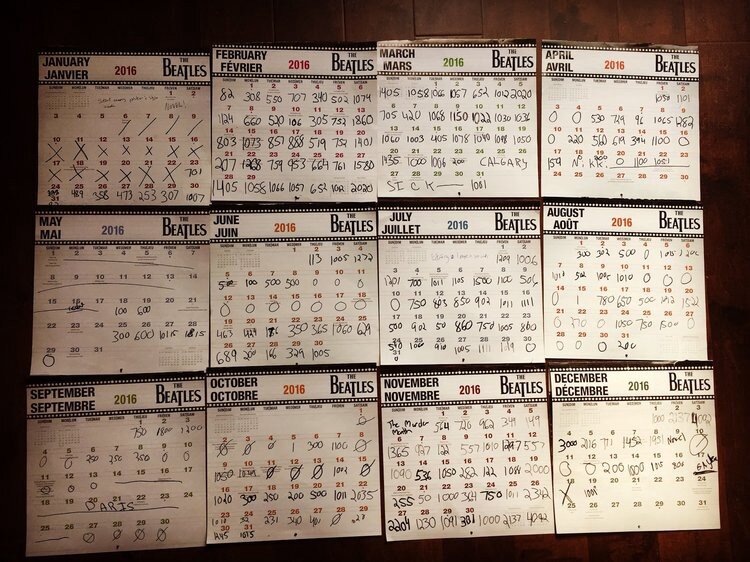

That’s a calendar of when I started writing my first novel. I discovered the wonderful way tracking your progress motivates you to do it daily. I originally was doing an X, if I both read and wrote every day, and a line if I only did one. Then I moved to word counts, which was huge. It became a competition with myself to get those word counts up.

Journaling. I would go as far to say that journaling is what caused me to become a serious writer. I almost entirely use my journal to track what hurts my writing, what helps it, my thoughts on my writing, and simply planning my writing days. I also go back and read all my journals every year and it’s one of the most interesting things in the world to see where you’ve come from over the years.

Write at the same time every day. This is tricky and I’ve tried every time there is and come to the conclusion that the time of day doesn’t really matter, as long as it’s the same and you stick to it. Personally, I’ve found first thing in the morning is the easiest to stick to, but I don’t write as well. Evening is my best writing time, as in I’m the most mentally sharp, but it’s the hardest to stick to because life gets in the way. So I write in the morning, because doing the work is the most important thing to me.

Block out distractions. I use an app called “selfcontrol” which blocks websites. You cannot turn it off once you start, and you can set a timer. The big ones I block are Reddit, Facebook, Instagram, and Youtube. I also move my phone into another room, turn it off, or put it in a timed lockbox. Often, I’ll turn my phone off at night and won’t turn it back on until I’ve finished my daily word count in the morning.

Put it above all others. If you want to make it as a writer, you have to make it an important part of your life. You may want to go out with friends during your writing time, or stay out late and miss your morning time, but consistency is key and you should take it seriously.

Never miss a day, but if you do miss, which of course you will (you can see the zeros on my calendar days), NEVER miss two days in a row, which again you will.

Once you do miss a chunk of time writing, it’s going to be hard to start again. One of the best ways around this is to tell yourself to just write a single sentence and see how you feel. It’s like a runner who tells themselves they’re just going to put on their shoes, or walk around the block. You can trick your brain into starting by breaking it down into digestible parts. What you’ll find, thinking back to Ira Glass’s gap, is that it’s anxiety of sucking that is stopping you. You’re worried you’re going to suck, and often you are going to suck, and you don’t want to suck because we writers have fragile egos, so if you break it down into a digestible task, like a single sentence, the anxiety seems to dissipate.

It’s a marathon not a sprint. Work your way up. Whenever I take some time off writing, I look at it like training. You don’t just jump into a marathon, or you’ll find you won’t be able to walk for the next week. The same thing happens with writing. So, if you’re trying to build momentum and wrack up those consecutive days, tell yourself you’re just going to write anything for a week. One word, two words, whatever. Next week, 250 words. The next week, 500. And so on, until you hit what you think is a reasonable, normal number, which for most people is around 1000 words a day.

Finally, find what works for you. Everyone is different. Some people like listening to music, or writing in a public setting, or, like Brandon Sanderson, walking on a treadmill while writing. This also may be where your journal comes in. Investigate what you like and don’t like and what helps you write more.

Writing

I won’t focus too much on the actual act of writing and writing well, because that’s too gargantuan of a subject for an already long article. I’ll just say some very preliminary basics.

Find out if you’re a gardener or an architect. George R.R. Martin, the creator of Game of Thrones, explained the difference this way: “The architects plan everything ahead of time, like an architect building a house. They know how many rooms are going to be in the house, what kind of roof they’re going to have, where the wires are going to run, what kind of plumbing there’s going to be. They have the whole thing designed and blueprinted out before they even nail the first board up. The gardeners dig a hole, drop in a seed and water it. They kind of know what seed it is, they know if planted a fantasy seed or mystery seed or whatever. But as the plant comes up and they water it, they don’t know how many branches it’s going to have, they find out as it grows. And I’m much more a gardener than an architect.”

You will suck. That’s a given. But remember The Gap. Practice will get you through it. But because you will suck, that practice is going to take an emotional toll on you. You’re going to struggle to write that sentence while hating that very same sentence you’re writing.

This is where “Bird by Bird” by Anne Lamott comes in. Her father, when she was a child, had told her brother to take his essay on birds “Bird by Bird” to get to the end. So write your story bird by bird, word by word, sentence by sentence. The second part of this advice is do not read your first draft until it’s done. I can’t stress that enough. It will be painful and it will demotivate you. Simply get it down then make it better.

Third, and again some people may disagree with me, but this is my experience: write short stories before novels. You want to finish something and go through the full process of creating a story, through multiple drafts and edits. If you start a novel, you’ll very likely give up before you get to the later stages that go into creating a piece of fiction. Get ten or so short stories under your belt.

Editing

Good books are made in the editing process. Here’s mine, but your mileage may vary.

Write your first draft. Remember! Don’t look back. Just get it out there. You’re doing nothing here but telling yourself the story.

Go over your first draft and make sure the story is exactly as you want it — a lot of the time, after you’ve written the first draft, you realize some things don’t work, or development is missing, or you wrote scenes that didn’t need to be included. Trim or add here.

Rewrite the story, filling in any missing parts or overarching story changes, or removing parts that don’t work. Personally, I love to rewrite, as this is how many brain works. In total, I like 3 full rewrites, and I use this time to crystallize the story in my mind. Every time I rewrite it, I see the characters as more real, and the scenes as more vivid, and it makes the writing come across better. It might be overkill, but I feel it’s necessary.

Okay, now that your story is exactly as you want it, print it off. Hand-edit it, line by line. I find a new medium helps see it in a new light.

Transfer that hand-edit back into a third draft (your third rewrite). On this draft, since the story is now exactly as I want it, I’m focusing on my word choice, sentence style, and voice.

Next, read it out loud, and edit as as you go. Again, hearing it out loud is a new medium and you’ll notice things you didn’t before.

Finally, clean up duty. Use Command + F to search the document for words that you over-use, or too many ‘ly’ adjectives, or to look for ‘by’ to find passive sentence structures, and so on. While writing, and this is a tip I probably should have said earlier, make sure to keep a list of words you don’t like or you feel like you’re using too much. For example, in my last novel I felt like I was using eyebrows or precipice too much. So in my last run through, I found them all and removed a few of them that I felt didn’t work.

And after that, I think you will have a novel that’s ready to be beta-read by others.

Reading fiction

If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have time to write. Simple as that — but what’s more, I assume you want to write because you love to read, you love stories, you love fiction. If you didn’t, why would you be here?

The best advice I can give is read a lot, read what you want to write, and study the books that produce something in you. That can be good or bad. It’s why I like editing novels and doing first readings for literary journals. I want to read what not to do as well as what to do.

If you feel like you’re not getting enough out of the books you read, I can recommend two books that will help: The Art of X-Ray Reading by Roy Peter Clark and Reading Like A Writer by Francine Prose. Those will break down how to close read and how to learn from what you’re reading to improve your own writing.

Reading books on writing

The last part of your writing practice — reading about writing.

I find reading about writing is one of the easiest ways to get over my writing anxiety. When I’m feeling particularly down or uninspired, when I’m feeling untalented or like a hack, I pick up a book on writing. Armed with a little knowledge, I find my words flow a bit better.

NOTE: some people can get addicted to reading about writing over writing. The single most important thing you can do is write. Then it’s read fiction or books that are similar to what you want to write, then read books about writing.

But if you’re just starting out, you might be wondering where to start?

Is it on dialogue, plot, character, voice, or something more general?

A lot of people aren’t going to like this, but to me, the most important book to read, before anything else is a book on Grammar. Even if you know it, or think you have a pretty good grasp on it, I think it’s incredibly important to hone those base skills. It’s the same way a guitarist will learn scales or chords when they first begin.

Now there’s a lot of books on grammar, like The Elements of Style or Eats, Shoots, Leaves, but my particular favourite is a relatively short textbook called Rhetorical Grammar: Grammatical Choices and Rhetorical Effects by Martha Kollin and Loretta Gray.

What I like about it is it not only provides you with a deep understanding of the fundamentals of a sentence and grammar, but it’ll teach you other things like showing vs telling, using details, being sparse with adverbs or adjectives, the cardinal sins of bad writing, and so on. I really do think this is a foundational text for any writer.

Some other great books to read are:

Dialogue by Robert McKee or The Fiction Writer’s Guide to Dialogue by John Hough Jr.

Self-Editing for Fiction Writers by Rennie Browne & Dave King

James Scott Bell also has a great lecture series called “How To Write Best Selling Fiction”

and KM Weiland has a few good audiobooks I’ve listened to.

And that’s the four pillars that go into a writing practice, and how you will get better at writing.

So, in conclusion, can writing be taught?

I’ll let John Barth, who taught for twenty-two years in the Writing Seminars at John Hopkins, answer that question, because he answered it as simply and emphatically as one could.

“It can, because it is.”