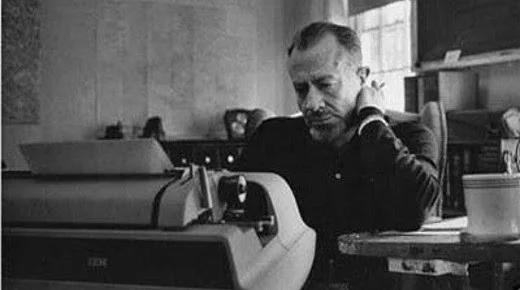

What Is The True Goal Of A Writer? - The Art Of Fiction by John Gardner

It was 2:30 pm on a Tuesday in September when the sound of a harley bounced off the sparse pine trees of Route 92 two miles from Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania. There was the screech of rubber on freshly-oiled gravel, a crash, then silence. A half hour later, on September 14th, 1982, John Gardner was pronounced dead from blunt force trauma.

He was a literary critic, father, poet, novelist, and a teacher—the latter being, to me and I’m sure the thousands of students and readers he’s touched, his most important impact on the literary world.

He loved fiction and took the gift he was given seriously. His view of art, and by extension fiction, could be summed up by this quote, appearing in his work, “On Moral Fiction,” where he wrote, “Almost all modern art is tinny, commercial and immoral. Let a state of total war be declared not between art and society but between the age-old enemies, real and fake.”

And in his book, “The Art of Fiction: Notes On Craft For Young Writers” that passion for fiction comes across. When I first read it, it was like a light bulb went off and I suddenly had a better conception of what we as writers are trying to do.

Simply put, we are creating a “dream-like” state in the reader, where they play a film in their minds. This concept wasn’t something I had heard before when I read it four years ago. It was something that I knew could happen from my own experiences as a reader. I remember those few times when I would get lost within the pages, unaware that I was reading, because the film in my mind had taken over and the words I read on the page were simply being filtered into pictures in my brain. It was automatic and pleasurable and few and far between.

It’s both surprising and unsurprising how rare those moments were when I think back to my life-long reading habit. It’s surprising because that’s the goal of the writer, to make us fall into these dreamlike states. It’s not surprising because it’s difficult to achieve the effect consistently.

As an example, I recently picked up the book that opens with five men discussing a prior event without context, which I cannot imagine, because I don’t understand what they’re talking about. The next chapter is one of the men’s wife, who gives about 15 pages of background on her and her life and the man. The next chapter is the wife’s life, who again gives another 10 pages of background info. All three of these chapters, which comprise about 50 pages of the novel, are almost without scene, as all three refer to other points in time and the main character tells the reader about those times.

This is an extreme example of showing versus telling, where characters tell the reader about themselves, but the author does very little to show us the scenes or make us understand the character through scenes. Our inner mental engine, that movie projector behind our eyes, has no film to run on. We simply cannot imagine what’s happening and what we’re left with are characters and stories without context or a reason to care.

It reminds me of that George Constanza quote, where he goes into the NBC office and tells them about the “story about nothing” and the head of NBC, Russell Dalrymple, asks him why they’re watching it. “Because it’s on TV!” he replies. And that’s not good enough. Your audience isn’t going to slug through two hours of exposition to get to a story. You don’t need to give background to your story before you give a story because what will happen is exactly what happened with this aforementioned story, I shut the book and moved on.

Luckily, I moved onto a book that opened in a much different manner. It was Michael Redhills, “Bellevue Square,” which opens, “My Doppelgänger problems began one afternoon in early April” followed by an immediate scene that gives us context to the line, the main character, who she is, and what the book will be about without directly telling us. It was a chapter and a first line that made me audibly sale “now that’s how you start a novel.”

But to return to John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction—How do you turn on that projector?

His first tip is verisimilitude: making the reader believe that the things they are reading happened or could, if the world or life or the laws of physics were a little bit different. Because what you’re doing with a story is, well, telling a story. You don’t set out to ‘express yourself’ when you tell a story. You ‘express yourself’ through your story, so your first goal is to tell a convincing story. Self-expression is a product of a good story, not a goal in and of itself.

He argues that any writer worth his salt will need, as a basis for his writing, two things in order to hope to achieve verisimilitude:

One, they must have an understanding of others and a trust in their own ability to judge, which is rooted in their own wisdom, generosity, compassion, strength of will, so that when others see an idea, they say to themselves, “Yes, you’re right, that’s how it is!”

Two, they should have an absolute trust in their own aesthetic judgements, both in the world around them and in their ability to reproduce those things in writing.

What this means is that the writer must read widely and write consistently, because practice is as much a requirement of the writer as it is for any other skill. They must be on a constant lookout for those sentences that turn the fan of your mental projector, or those that fail, and understand why they fail.

For a blog about reading, read my blog, “Read like a Writer” here.

Why do you need the above two qualities? Because, as John Gardner says, “vivid detail is the life blood of fiction.”

That is, in order to achieve an outer strategy of verisimilitude, an inner strategy of well-placed and ostenbily innocuous details is how you convince the reader that what is happening on the page is really happening.

To use my above example of Redhill’s “Bellevue Square,” I came across this detail about a character: “Beatrice’s tongue is pinned to the floor of her mouth owing to some childhood incident involving a pencil, so you only ever see the pristine pink tip of it.”

This rather specific detail, which seems almost too odd to imagine up, convinces the reader that this character is, in fact, a real person with thoughts and dreams and fears. This is how you use imaginative “innocuous” detail to convince your reader. It is these details that prove the actuality of a scene.

If you have it nearby, or you have a work of fiction nearby, pick it up and examine it for these details. Once you realize what to look for, you’ll notice somewhere between 20-40% of the words of a text are (generally) devoted to convincing the reader that this is happening through vivid detail.

What Vivid Details Should A Writer Include?

Now, the tricky part comes into play when you ask yourself: what details should I include? It’s also why you must read widely and trust that your writerly instincts are correct. On paper, look for those details and ask yourself, “Why did the writer choose this detail and not another?” Go out into the wild (that place outside) and take in people’s exteriors and ask yourself, “what’s one item or characteristic that could encapsulate this person fully.”

One of my favourite examples, but sadly the origin escapes me, is the example of the man who got into his truck wearing a torn and oil-stained John Deere baseball cap. That’s one aspect of who the man is, but we feel, from that vivid detail, that we get a sense of him. We can guess at his politics, his beliefs, and his age. We may even put a face to the hat, without knowing it. That’s because that hat is a symbol for other ideas that already exist in our head. It allows us to latch onto it and creates an image that we can imagine, pulling from our own subconscious.

What you want to do is figure out other symbols for each of your characters that will easily point out who the characters are and what they believe in. It also doesn’t mean you have to make those characters believe those things, or be that way, as a symbol turned on its head can be interesting.

Now, John Gardner’s book, “The Art Of Fiction” does not stop there. Vivid imagery and verisimilitude only encompasses 39 pages of a 200 page book, but it was the “vivid image” that stuck out in my mind long after I finished the book, and it has given me a lasting impression on what a strong, vivid detail can do for you.

Another great book, one that may go into this idea deeper, is Robert Olen Butler’s book on writing, “From Where You Dream.” He talks about an exercise where he gets his students to tell a story ONLY using sensory details, which I’ve been meaning to try.

But more than that, he goes into the idea of this dream-state and how to achieve it.